The Iowa Nest is a Net Zero Energy-targeted residence in rural Iowa. It is designed to supply 100% of its energy needs; to be comfortable without conventional air conditioning; to fit into the landscape; to last for hundreds of years; and to do all of this on a conventional construction budget.

This blog will be run jointly by me (Carl), the primary designer, and by the owners, Peter and Jen. Our hope is to share our experiences designing and building this house so others can learn from our mistakes and re-create our successes. Our experience has shown us that it is possible to achieve remarkable performance (and great design) with a reasonable budget — and we hope to show others how they can do this, too.

You can subscribe to our mailing list to get regular updates: just send an email to list@iowanest.com.

Let’s start by taking a closer look at the project’s design goals.

Net Zero Energy

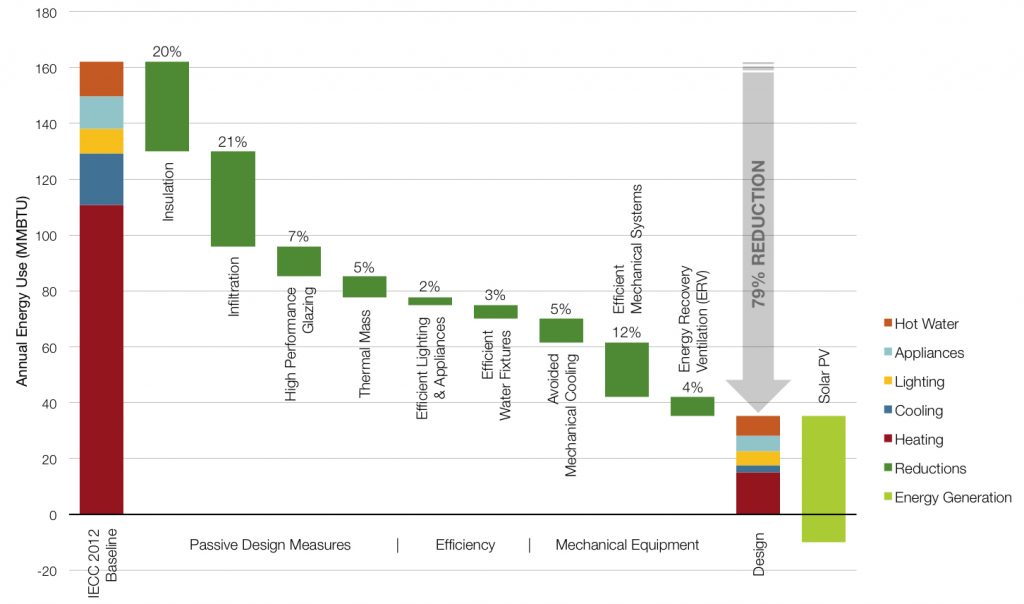

The building will produce as much energy as it requires on an annual basis with on-site solar photovoltaic panels mounted to the roof. The house will be grid-tied: it will contribute back to the grid at some times, and draw from it at others.

In order to make solar practical, the house is designed to achieve an 80% reduction in energy use compared to a conventional new home (specifically, an IECC 2012 code baseline).

Conventional Cost

The house is designed to achieve the same per-square-foot cost as conventional new residential construction in Iowa. The website Building Journal puts this at about $130 per square foot; at the time of this writing (August 2016) the house is on track for $128/sq.ft. (this cost is “all-in” meaning it includes all design fees in addition to the solar array and inverter). Major cost-saving strategies include: a compact building form, cost-effective materials — specifically ICF walls and roof, which provide multiple benefits with a single material — standard (rather than luxury) interior finishes, cost-effective mechanical systems, and careful cost control during construction.

Passive Cooling / No Air Conditioning

While Iowa is considered a “cold” climate, with ~6000 heating degree days and a deep, frigid winter, it nonetheless has hot and extremely humid summers, with temperatures exceeding 100 degrees F and 90% relative humidity during the worst weeks. This seasonal duality can make passive design a challenge — but one we felt compelled to take on.

Why? Partly it’s about the energy goals: achieving Net Zero, and not using energy unnecessarily. Partly it’s about capital cost: not building superfluous systems, or investing in systems that are only needed for a small fraction of annual hours. But I think it’s important for another reason: our experience of the natural world. There is something satisfying — indeed, deeply nourishing — about experiencing the seasons — about changing our behaviors in response to the world around us — about sitting in the shade against a cool wall in the summer, and snuggling under a blanket with a large cat on your lap in the winter. Our modern life and worldview have insulated us against the natural world, and I believe we must reconnect at a visceral level if we want to forge a sustainable path forward.

I will write more about how the design achieves comfort for an estimated 96% of occupied hours without AC — but the short version is “good passive design” — methods that have been with us for millennia. That includes a partially underground house (the ground stays at a pleasant 60 degrees F during the summer months); high thermal mass to mitigate temperature swings in the fall and spring; natural ventilation (including night-flush ventilation); shading (both fixed and operable); deciduous trees to the west, to protect against harsh late-afternoon sun; and good daylighting to obviate the need for electric lights (and the heat they produce) during the hottest daytime hours.

Finally, the house is designed so that a whole-house dehumidifier and/or a mini-split system could easily be added later should it become necessary. The plan is to evaluate the design in the first year(s) of operation and see if our comfort models (and climate assumptions) were accurate.

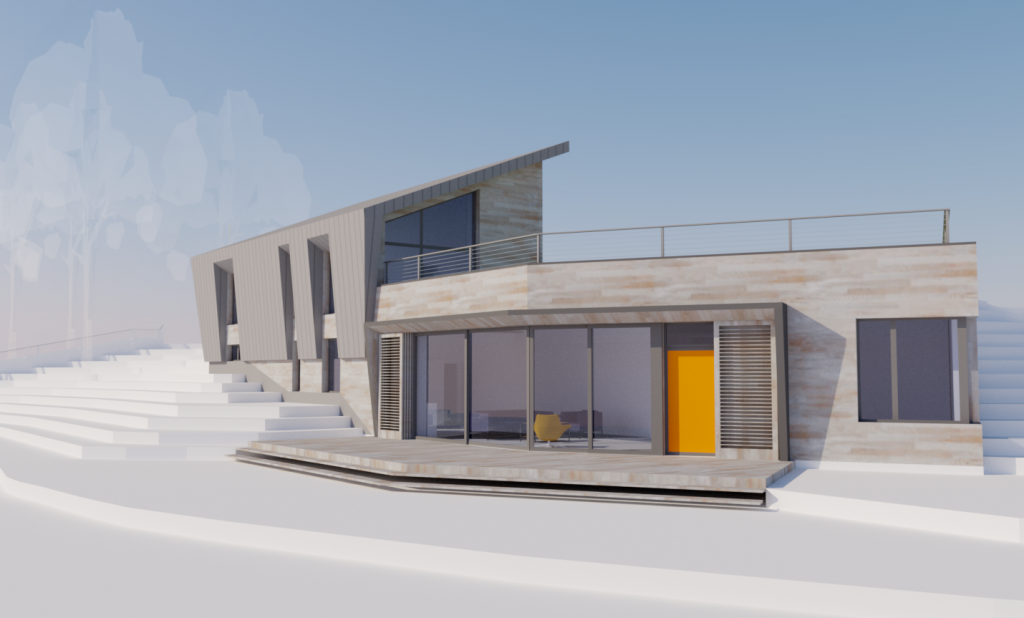

Integrated with the land

The house is built into a south-facing hillside in an abandoned quarry, looking over a meadow the to south and a lake to the east. Native meadow grasses cover the lower roof. Weathered wood cladding and metal roofing evoke vernacular farm buildings, and create a natural counterpoint to the surroundings. Generous operable windows and doors (with insect screens!) enable the house to open up when weather permits.

A 200-Year House

Construction is a high-embodied-energy activity; in order to justify this investment, our buildings should be designed to last for centuries.

The longevity of a building is due to several factors: use of durable materials (here, a largely concrete envelope), careful detailing to control water and moisture, and a flexible interior layout (including design for aging in place). I will write more on these strategies in future posts.

But durability is also about beauty — often overlooked but critically important. A building must be loved. It must be inviting, comfortable, whole. It must change gracefully with the seasons, inspiring joy and a sense of belonging. These are the buildings that last: the ones judged worthwhile to preserve. This house aims for such beauty.

We’ll elaborate on each of these areas in future posts. Email list@iowanest.com to join the Iowa Nest Residence mailing list.

Interested in volunteering to help with any part of the build? Email build@iowanest.com.

Looks great Carl! I’m looking forward to watching the progress. I hope you dive into the project costs in more detail in a future post. I am skeptically curious how you are acheiving such a low “all-in” cost per square foot on a compact design, with a PV system. Take care!

Yes, we plan to go into much more detail on the project costs. I appreciate your skepticism — it’s taken a lot of work (and more than one redesign) to get where we are … and it’s still under construction, so we’re not there yet!

Let me just mention a few things:

1. ICF construction. It’s slightly more expensive than conventional stick-built construction, but provides multiple benefits. We could get the R-values we wanted for walls & roofs, and the concrete itself is an air barrier, which means we didn’t have to buy expensive air barrier membranes.

2. Careful sourcing. We got a lot of competing bids from different suppliers and manufacturers, especially for expensive line items (in our case, waterproofing and green roof was a big one, as were ICFs and windows).

3. Working with suppliers. We pushed suppliers for creative solutions that we might have missed. For example, while we spent a hefty sum for Zola Windows, the project managers there were extremely helpful in making sure that we didn’t spend needlessly — they helped me understand what drove the cost, and we made a number of revisions to bring the window package within budget without sacrificing the special moments (the big south sliders or the angled window in the study).

4. Efficient design. There are some simple things that can apply to any house. For instance, if you look at the plans you’ll notice that all of the plumbing is along a single wet wall, which greatly simplified plumbing.

5. A great team. We found a structural engineer who had done a ton of ICF work, and he more than paid for himself in cost savings that he identified. Similarly, we had a great mechanical engineer, who suggested that, because our heating loads were so low, we should consider an electric radiant system — which ended up being less than half the cost of the ground source heat pump that we’d originally planned to use.

This is an incomplete list, but hopefully begins to illustrate how we did this. As I said, we’ll try to write more in future posts …

Are there any more renders/plans/views of the house itself?

I just posted some drawings here: http://www.iowanest.com/index.php/2016/09/30/plans-elevations/

Carl,

I’m glad I found this blog about your beautiful and efficient project. I will be coordinating an interdisciplinary team of Miami U. students in the design of Net Zero Energy home or multifamily housing this Spring. This house will make an excellent case study precedent for them!

Best regards,

Mary Ben

Thank you Mary Ben! Let me know if there’s any way I can help out with your studio — it sounds great! It’s going to be so essential for architecture grads to understand the nuts & bolts of net zero design …

I am very intrigued about this project. I co-run the Sustainable Construction and Design program at Hawkeye Community College and would love to bring the students to view this project and have you present if you would be interested.

Thanks for your interest! I’ll be in touch by email about organizing a presentation or tour.

Hello Carl, I read your article on the net zero home and was wondering if you still feel the cost per square foot is working out in todays market. Can you tell me what the cost per square foot would be to a 1300 square foot net zero home?

Carl – I just stumbled onto your project in the 13th edition of MEEB. Great work. Hope you get to Passive Haus. Looks great.

Joel, thank you, most appreciated. I’m a huge fan of the Center for Integrated Design’s work, and particularly the recent work from the Carbon Leadership Forum.